The Iberville development, nestled on a ten-block site in the early 1940s as part of the Wagner Bill, has a history more intricate than meets the eye. It’s a history intertwined with New Orleans’ rich and enigmatic past, a past that I didn’t personally live through, but my family and friends did. For them, the Iberville wasn’t just a place to call home; it was a testament to an era that was never spoken of, an era dominated by secrecy and the passage of time.

As I reflect on those days, a single sign stands out in my memory. An unassuming marker at the project’s entrance, it bore no significance in our daily lives. It simply was there, like an old friend silently witnessing the passage of time. I never thought to inquire about it, and neither did my family. It was just another fixture in the backdrop of our lives.

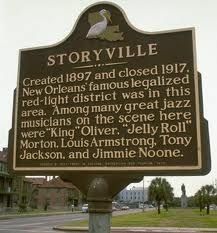

The name “Iberville” occasionally made me ponder. It brought to mind memories of “Storyland” at City Park—a place I adored. Storyland was a realm of whimsical characters, thrilling rides, delectable food, and an enchanting atmosphere that still warms my heart. In contrast, my research into Storyville, the district the Iberville once occupied, revealed a stark contrast. Storyville was New Orleans’ official red-light district—a world apart from the innocence of Storyland. Both held their unique allure, but the Iberville project, with its family connections and intriguing history, seemed to straddle the line between the two worlds.

The Iberville wasn’t just bricks and mortar; it was a place of memories and experiences. I recall the peculiar sights within its confines, like a used tire hanging from a tree or the daring thrill of a ride in a mock police car to the “jail.” The level of excitement depended on whether the car’s lights were flashing, allowing us to choose our own imaginary crime.

One sign, though, has left me questioning not only the Iberville but also the broader context of our history. This particular sign, or rather, a nondescript plaque—a slab of concrete adorned with vague information—haunts my thoughts. For years, I failed to notice a crucial detail: it marked the location of a legalized red-light district. It’s as if the writer or influential decision-maker deliberately obscured this fact, knowing that not just I, but many others, would overlook it.

In my youthful imagination, I envisioned the Iberville as a place where jazz legends and greats once lived and performed. Yet, I now know that the majority of its residents came from deeply spiritual families. The mere notion of dwelling in a former brothel district would have been unthinkable to their grandmothers. This revelation forces me to question the authenticity of the sign’s history. Was it fabricated to keep families from leaving?

Why were we kept in the dark about our own history, misinformed, and ignorant of the truth? Why was this history scrubbed from our collective memory and rewritten to fit a different narrative?

In recent years, I’ve come to understand that public housing projects weren’t primarily designed to uplift poor Black people; they were often constructed to serve the interests of whites. These projects, along with stores, restaurants, and more, were intentionally segregated, a practice that still persists. Even today, if you visit a corner store in a Black neighborhood, it’s likely owned by someone from a different racial background, profiting from our communities without residing within them. Why is this the case?

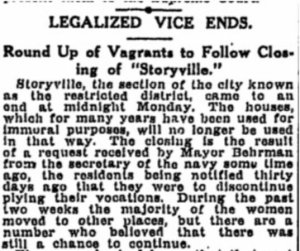

Discovering that the Iberville’s location was originally mapped for legal prostitution and control has shed light on a broader pattern of manipulation. Storyville, once a project before projects existed, illustrates how the government has always maintained control over who, what, when, and where. They exploit these controlled environments until they spiral out of control, at which point they label them as illegal.

Storyville and the Iberville have faded into history, much like the brick and mortar that once defined them. However, the legacy of control and exploitation continues, even without the physical structures. Rising living costs coupled with stagnant wages have kept many trapped in the same circumstances. Acts of nature like Katrina and Harvey occasionally disrupt the status quo, but they also reveal the enduring inequality that persists.

To those who never left New Orleans, the projects, or the hood, I hope you’ve found a path to better living wherever you are. But let us not turn a blind eye to our history, blindly trust what is written or said, and continue the cycle of ignorance. Instead, let’s embark on a journey of self-education and share our knowledge with our families and communities.

Did you know that the Iberville was once the heart of legalized prostitution? Were you aware that “colored women” could work in the brothels, while “colored men” couldn’t purchase pleasure from either white or Black women? A Black man couldn’t even pay for such services, but he could find employment in the brothels and nightclubs. It seems that’s where the roots of jazz truly lie—a complex and tangled history that deserves to be unraveled and understood.

Today, the Iberville may be gone, but its legacy endures. The district has undergone transformation and rebirth, now known as the Bienville Basin Apartments complex. It stands as a symbol of resilience, reminding us of the strength and determination of those who lived within its boundaries.

Yet, there’s another chapter in this story—a chapter that speaks of change and the relentless march of progress. In recent years, New Orleans has seen the sale of one of the few remaining housing projects. This sale marked a significant shift in the city’s landscape, as the property’s new owners had ambitious plans for its redevelopment.

It seems like an attempt to profit off the major contributions from African American culture, including our rich death rituals and traditions. Yet, amidst these changes, the memories of hanging out with friends in the court, using the cemetery wall for impromptu gymnastics, and gathering at a friend’s apartment in the Iberville before embarking on adventures in the French Quarter, the Pennyland Arcade, the Lowe’s theater, and indulging in cheap eats and shopping on Canal Street, remain as vibrant as ever. These were the moments that defined our youth, filled with laughter and camaraderie.

As the old housing project gave way to transformation, the fabric of these lives also began to change. The stories of resilience and survival now intersect with those of adaptability and the quest for a brighter future.

As we remember the Iberville and Storyville, let’s also reflect on the broader context of our history, acknowledging both the shadows and the triumphs that have shaped our community.

Iberville street sign

Excellent information! Maybe most do not know.

LikeLike